Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American clergyman, activist, and prominent leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement.[1] He is best known for his role in the advancement of civil rights in the United States and around the world, using nonviolent methods following the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi.[2] King has become a national icon in the history of modern American liberalism.[3]

A Baptist minister, King became a civil rights activist early in his career.[4] He led the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott and helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, serving as its first president. King's efforts led to the 1963 March on Washington, where King delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. There, he expanded American values to include the vision of a color blind society, and established his reputation as one of the greatest orators in American history.

In 1964, King became the youngest person to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to end racial segregation and racial discrimination through civil disobedience and other nonviolent means. By the time of his death in 1968, he had refocused his efforts on ending poverty and stopping the Vietnam War.

King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee. He was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977 and Congressional Gold Medal in 2004; Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was established as a U.S. federal holiday in 1986

King was originally skeptical of many of Christianity's claims.[8] Most striking, perhaps, was his initial denial of the bodily resurrection of Jesus during Sunday school at the age of thirteen. From this point, he stated, "doubts began to spring forth unrelentingly".[9] However, he later concluded that the Bible has "many profound truths which one cannot escape" and decided to enter the seminary.[8]

Growing up in Atlanta, King attended Booker T. Washington High School. A precocious student, he skipped both the ninth and the twelfth grade and entered Morehouse College at age fifteen without formally graduating from high school.[10] In 1948, he graduated from Morehouse with a Bachelor of Arts degree in sociology, and enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, from which he graduated with a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1951.[11][12] King married Coretta Scott, on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her parents' house in her hometown of Heiberger, Alabama.[13] They became the parents of four children; Yolanda King, Martin Luther King III, Dexter Scott King, and Bernice King.[14] King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, when he was twenty-five years old, in 1954.[15] King then began doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University and received his Doctor of Philosophy on June 5, 1955, with a dissertation on "A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman". A 1980s inquiry concluded portions of his dissertation had been plagiarized and he had acted improperly but that his dissertation still "makes an intelligent contribution to scholarship",[16][17][18]

In a 1958 interview, he expressed his view that neither party was perfect, saying, "I don't think the Republican party is a party full of the almighty God nor is the Democratic party. They both have weaknesses ... And I'm not inextricably bound to either party."[30]

King critiqued both parties' performance on promoting racial equality:

In his autobiography, King says that in 1960 he privately voted for Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy: "I felt that Kennedy would make the best president. I never came out with an endorsement. My father did, but I never made one." King adds that he likely would have made an exception to his non-endorsement policy in 1964, saying "Had President Kennedy lived, I would probably have endorsed him in 1964.

On September 20, 1958, while signing copies of his book Stride Toward Freedom in Blumstein's department store on 125th Street, in Harlem,[44][45] King was stabbed in the chest with a letter opener by Izola Curry, a deranged black woman, and narrowly escaped death.[46]

Gandhi's nonviolent techniques were useful to King's campaign to change the civil rights laws implemented in Alabama.[47] King applied non-violent philosophy to the protests organized by the SCLC. In 1959, he wrote The Measure of A Man, from which the piece What is Man?, an attempt to sketch the optimal political, social, and economic structure of society, is derived.[48] His SCLC secretary and personal assistant in this period was Dora McDonald.

The FBI, under written directive from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began telephone tapping King in the fall of 1963.[49] Concerned that allegations (of Communists in the SCLC), if made public, would derail the Administration's civil rights initiatives, Kennedy warned King to discontinue the suspect associations, and later felt compelled to issue the written directive authorizing the FBI to wiretap King and other leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.[50] J Edgar Hoover feared Communists were trying to infiltrate the Civil Rights Movement, but when no such evidence emerged, the bureau used the incidental details caught on tape over the next five years in attempts to force King out of the preeminent leadership position.[51]

King believed that organized, nonviolent protest against the system of southern segregation known as Jim Crow laws would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality and voting rights. Journalistic accounts and televised footage of the daily deprivation and indignities suffered by southern blacks, and of segregationist violence and harassment of civil rights workers and marchers, produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that convinced the majority of Americans that the Civil Rights Movement was the most important issue in American politics in the early 1960s.[52][53]

King organized and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights and other basic civil rights.[42]:85 Most of these rights were successfully enacted into the law of the United States with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.[54][55]

King and the SCLC put into practice many of the principles of the Christian Left and applied the tactics of nonviolent protest with great success by strategically choosing the method of protest and the places in which protests were carried out. There were often dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities. Sometimes these confrontations turned violent.[56]:190

After nearly a year of intense activism with few tangible results, the movement began to deteriorate. King requested a halt to all demonstrations and a "Day of Penance" to promote non-violence and maintain the moral high ground. Divisions within the black community and the canny, low-key response by local government defeated efforts.[56]:190–3 However, it was credited as a key lesson in tactics for the national civil rights movement.[57]

Protests in Birmingham began with a boycott to pressure businesses to offer sales jobs and other employment to people of all races, as well as to end segregated facilities in the stores. When business leaders resisted the boycott, King and the SCLC began what they termed Project C, a series of sit-ins and marches intended to provoke arrest. After the campaign ran low on adult volunteers, SCLC's strategist, James Bevel, initiated the action and recruited the children for what became known as the "Children's Crusade". During the protests, the Birmingham Police Department, led by Eugene "Bull" Connor, used high-pressure water jets and police dogs to control protesters, including children. Not all of the demonstrators were peaceful, despite the avowed intentions of the SCLC. In some cases, bystanders attacked the police, who responded with force. King and the SCLC were criticized for putting children in harm's way. By the end of the campaign, King's reputation improved immensely, Connor lost his job, the "Jim Crow" signs in Birmingham came down, and public places became more open to blacks.[59]

King and the SCLC joined forces with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Selma, Alabama, in December 1964, where SNCC had been working on voter registration for several months.[61] A sweeping injunction issued by a local judge barred any gathering of 3 or more people under sponsorship of SNCC, SCLC, or DCVL, or with the involvement of 41 named civil rights leaders. This injunction temporarily halted civil rights activity until King defied it by speaking at Brown Chapel on January 2, 1965.[62]

The march originally was conceived as an event to dramatize the desperate condition of blacks in the southern United States and a very public opportunity to place organizers' concerns and grievances squarely before the seat of power in the nation's capital. Organizers intended to denounce and then challenge the federal government for its failure to safeguard the civil rights and physical safety of civil rights workers and blacks, generally, in the South. However, the group acquiesced to presidential pressure and influence, and the event ultimately took on a far less strident tone.[68] As a result, some civil rights activists felt it presented an inaccurate, sanitized pageant of racial harmony; Malcolm X called it the "Farce on Washington," and the Nation of Islam forbade its members from attending the march.

The march originally was conceived as an event to dramatize the desperate condition of blacks in the southern United States and a very public opportunity to place organizers' concerns and grievances squarely before the seat of power in the nation's capital. Organizers intended to denounce and then challenge the federal government for its failure to safeguard the civil rights and physical safety of civil rights workers and blacks, generally, in the South. However, the group acquiesced to presidential pressure and influence, and the event ultimately took on a far less strident tone.[68] As a result, some civil rights activists felt it presented an inaccurate, sanitized pageant of racial harmony; Malcolm X called it the "Farce on Washington," and the Nation of Islam forbade its members from attending the march.

The march did, however, make specific demands: an end to racial segregation in public schools; meaningful civil rights legislation, including a law prohibiting racial discrimination in employment; protection of civil rights workers from police brutality; a $2 minimum wage for all workers; and self-government for Washington, D.C., then governed by congressional committee.[70][71][72] Despite tensions, the march was a resounding success. More than a quarter million people of diverse ethnicities attended the event, sprawling from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial onto the National Mall and around the reflecting pool. At the time, it was the largest gathering of protesters in Washington's history.[73] King's "I Have a Dream" speech electrified the crowd. It is regarded, along with Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address and Franklin D. Roosevelt's Infamy Speech, as one of the finest speeches in the history of American oratory.[74]

The March, and especially King's speech, helped put civil rights at the very top of the liberal political agenda in the United States and facilitated passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

A Baptist minister, King became a civil rights activist early in his career.[4] He led the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott and helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, serving as its first president. King's efforts led to the 1963 March on Washington, where King delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. There, he expanded American values to include the vision of a color blind society, and established his reputation as one of the greatest orators in American history.

In 1964, King became the youngest person to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to end racial segregation and racial discrimination through civil disobedience and other nonviolent means. By the time of his death in 1968, he had refocused his efforts on ending poverty and stopping the Vietnam War.

King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee. He was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977 and Congressional Gold Medal in 2004; Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was established as a U.S. federal holiday in 1986

Early life and education

For more details on this topic, see Martin Luther King, Jr. authorship issues.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, the middle child of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr. and Alberta Williams King.[5] King Jr. had an older sister, Willie Christine King, and a younger brother, Alfred Daniel Williams King.[6]:76 King sang with his church choir at the 1939 Atlanta premiere of the movie Gone with the Wind.[7]King was originally skeptical of many of Christianity's claims.[8] Most striking, perhaps, was his initial denial of the bodily resurrection of Jesus during Sunday school at the age of thirteen. From this point, he stated, "doubts began to spring forth unrelentingly".[9] However, he later concluded that the Bible has "many profound truths which one cannot escape" and decided to enter the seminary.[8]

Growing up in Atlanta, King attended Booker T. Washington High School. A precocious student, he skipped both the ninth and the twelfth grade and entered Morehouse College at age fifteen without formally graduating from high school.[10] In 1948, he graduated from Morehouse with a Bachelor of Arts degree in sociology, and enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, from which he graduated with a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1951.[11][12] King married Coretta Scott, on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her parents' house in her hometown of Heiberger, Alabama.[13] They became the parents of four children; Yolanda King, Martin Luther King III, Dexter Scott King, and Bernice King.[14] King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, when he was twenty-five years old, in 1954.[15] King then began doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University and received his Doctor of Philosophy on June 5, 1955, with a dissertation on "A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman". A 1980s inquiry concluded portions of his dissertation had been plagiarized and he had acted improperly but that his dissertation still "makes an intelligent contribution to scholarship",[16][17][18]

Influences

Thurman

Civil rights leader, theologian, and educator Howard Thurman was an early influence on King. A classmate of King's father at Morehouse College,[19] Thurman mentored the young King and his friends.[20] Thurman's missionary work had taken him abroad where he had met and conferred with Mahatma Gandhi.[21] When he was a student at Boston University, King often visited Thurman, who was the dean of Marsh Chapel.[22] Walter Fluker, who has studied Thurman's writings, has stated, "I don't believe you'd get a Martin Luther King, Jr. without a Howard Thurman".[23]Gandhi and Rustin

With assistance from the Quaker group the American Friends Service Committee, and inspired by Gandhi's success with non-violent activism, King visited Gandhi's birthplace in India in 1959.[6]:3 The trip to India affected King in a profound way, deepening his understanding of non-violent resistance and his commitment to America's struggle for civil rights. In a radio address made during his final evening in India, King reflected, "Since being in India, I am more convinced than ever before that the method of nonviolent resistance is the most potent weapon available to oppressed people in their struggle for justice and human dignity. In a real sense, Mahatma Gandhi embodied in his life certain universal principles that are inherent in the moral structure of the universe, and these principles are as inescapable as the law of gravitation."[6]:135–6 African American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin had studied Gandhi's teachings.[24] Rustin counseled King to dedicate himself to the principles of non-violence,[25] served as King's main advisor and mentor throughout his early activism,[26] and was the main organizer of the 1963 March on Washington.[27] Rustin's open homosexuality, support of democratic socialism, and his former ties to the Communist Party USA caused many white and African-American leaders to demand King distance himself from Rustin.[28]Public stance on political parties

As the leader of the SCLC, King maintained a policy of not publicly endorsing a U.S. political party or candidate: "I feel someone must remain in the position of non-alignment, so that he can look objectively at both parties and be the conscience of both—not the servant or master of either."[29]In a 1958 interview, he expressed his view that neither party was perfect, saying, "I don't think the Republican party is a party full of the almighty God nor is the Democratic party. They both have weaknesses ... And I'm not inextricably bound to either party."[30]

King critiqued both parties' performance on promoting racial equality:

Actually, the Negro has been betrayed by both the Republican and the Democratic party. The Democrats have betrayed him by capitulating to the whims and caprices of the Southern Dixiecrats. The Republicans have betrayed him by capitulating to the blatant hypocrisy of reactionary right wing northern Republicans. And this coalition of southern Dixiecrats and right wing reactionary northern Republicans defeats every bill and every move towards liberal legislation in the area of civil rights.[31]

Personal political advocacy

Although King never publicly supported a political party or candidate for president, in a letter to a civil rights supporter in October 1956 he said that he was undecided as to whether he would vote for the Adlai Stevenson or Dwight Eisenhower, but that "In the past I always voted the Democratic ticket."[32]In his autobiography, King says that in 1960 he privately voted for Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy: "I felt that Kennedy would make the best president. I never came out with an endorsement. My father did, but I never made one." King adds that he likely would have made an exception to his non-endorsement policy in 1964, saying "Had President Kennedy lived, I would probably have endorsed him in 1964.

Montgomery Bus Boycott, 1955

In March 1955, a fifteen-year-old school girl, Claudette Colvin, refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in compliance with the Jim Crow laws. King was on the committee from the Birmingham African-American community that looked into the case; because Colvin was pregnant and unmarried, E.D. Nixon and Clifford Durr decided to wait for a better case to pursue.[37] On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat.[38] The Montgomery Bus Boycott, urged and planned by Nixon and led by King, soon followed.[39] The boycott lasted for 385 days,[40] and the situation became so tense that King's house was bombed.[41] King was arrested during this campaign, which ended with a United States District Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle that ended racial segregation on all Montgomery public buses.[6]:9[42]:53Southern Christian Leadership Conference

In 1957, King, Ralph Abernathy, and other civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The group was created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct non-violent protests in the service of civil rights reform. King led the SCLC until his death.[43]On September 20, 1958, while signing copies of his book Stride Toward Freedom in Blumstein's department store on 125th Street, in Harlem,[44][45] King was stabbed in the chest with a letter opener by Izola Curry, a deranged black woman, and narrowly escaped death.[46]

Gandhi's nonviolent techniques were useful to King's campaign to change the civil rights laws implemented in Alabama.[47] King applied non-violent philosophy to the protests organized by the SCLC. In 1959, he wrote The Measure of A Man, from which the piece What is Man?, an attempt to sketch the optimal political, social, and economic structure of society, is derived.[48] His SCLC secretary and personal assistant in this period was Dora McDonald.

The FBI, under written directive from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, began telephone tapping King in the fall of 1963.[49] Concerned that allegations (of Communists in the SCLC), if made public, would derail the Administration's civil rights initiatives, Kennedy warned King to discontinue the suspect associations, and later felt compelled to issue the written directive authorizing the FBI to wiretap King and other leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.[50] J Edgar Hoover feared Communists were trying to infiltrate the Civil Rights Movement, but when no such evidence emerged, the bureau used the incidental details caught on tape over the next five years in attempts to force King out of the preeminent leadership position.[51]

King believed that organized, nonviolent protest against the system of southern segregation known as Jim Crow laws would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality and voting rights. Journalistic accounts and televised footage of the daily deprivation and indignities suffered by southern blacks, and of segregationist violence and harassment of civil rights workers and marchers, produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that convinced the majority of Americans that the Civil Rights Movement was the most important issue in American politics in the early 1960s.[52][53]

King organized and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights and other basic civil rights.[42]:85 Most of these rights were successfully enacted into the law of the United States with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.[54][55]

King and the SCLC put into practice many of the principles of the Christian Left and applied the tactics of nonviolent protest with great success by strategically choosing the method of protest and the places in which protests were carried out. There were often dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities. Sometimes these confrontations turned violent.[56]:190

Albany movement

Main article: Albany movement

The Albany Movement was a desegregation coalition formed in Albany, Georgia in November 1961. In December, King and the SCLC became involved. The movement mobilized thousands of citizens for a broad-front nonviolent attack on every aspect of segregation within the city and attracted nationwide attention. When King first visited on December 15, 1961, he "had planned to stay a day or so and return home after giving counsel."[9][page needed] But the following day he was swept up in a mass arrest of peaceful demonstrators, and he declined bail until the city made concessions. "Those agreements", said King, "were dishonored and violated by the city," as soon as he left town[9][page needed]. King returned in July 1962, and was sentenced to forty-five days in jail or a $178 fine. He chose jail. Three days into his sentence, Chief Pritchett discreetly arranged for King's fine to be paid and ordered his release. "We had witnessed persons being kicked off lunch counter stools... ejected from churches... and thrown into jail... But for the first time, we witnessed being kicked out of jail."[9][page needed]After nearly a year of intense activism with few tangible results, the movement began to deteriorate. King requested a halt to all demonstrations and a "Day of Penance" to promote non-violence and maintain the moral high ground. Divisions within the black community and the canny, low-key response by local government defeated efforts.[56]:190–3 However, it was credited as a key lesson in tactics for the national civil rights movement.[57]

Birmingham campaign

Main article: Birmingham campaign

The Birmingham campaign was a strategic effort by the SCLC to promote civil rights for African Americans. Many of its tactics of "Project C" were developed by Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, Executive Director of SCLC from 1960–64. Based on actions in Birmingham, Alabama, its goal was to end the city's segregated civil and discriminatory economic policies. The campaign lasted for more than two months in the spring of 1963. To provoke the police into filling the city's jails to overflowing, King and black citizens of Birmingham employed nonviolent tactics to flout laws they considered unfair. King summarized the philosophy of the Birmingham campaign when he said, "The purpose of ... direct action is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation".[58]Protests in Birmingham began with a boycott to pressure businesses to offer sales jobs and other employment to people of all races, as well as to end segregated facilities in the stores. When business leaders resisted the boycott, King and the SCLC began what they termed Project C, a series of sit-ins and marches intended to provoke arrest. After the campaign ran low on adult volunteers, SCLC's strategist, James Bevel, initiated the action and recruited the children for what became known as the "Children's Crusade". During the protests, the Birmingham Police Department, led by Eugene "Bull" Connor, used high-pressure water jets and police dogs to control protesters, including children. Not all of the demonstrators were peaceful, despite the avowed intentions of the SCLC. In some cases, bystanders attacked the police, who responded with force. King and the SCLC were criticized for putting children in harm's way. By the end of the campaign, King's reputation improved immensely, Connor lost his job, the "Jim Crow" signs in Birmingham came down, and public places became more open to blacks.[59]

St. Augustine, Florida, and Selma, Alabama

King and SCLC were also driving forces behind the protest in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1964.[60] The movement engaged in nightly marches in the city met by white segregationists who violently assaulted them. Hundreds of the marchers were arrested and jailed.King and the SCLC joined forces with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Selma, Alabama, in December 1964, where SNCC had been working on voter registration for several months.[61] A sweeping injunction issued by a local judge barred any gathering of 3 or more people under sponsorship of SNCC, SCLC, or DCVL, or with the involvement of 41 named civil rights leaders. This injunction temporarily halted civil rights activity until King defied it by speaking at Brown Chapel on January 2, 1965.[62]

March on Washington, 1963

Main article: March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

King, representing SCLC, was among the leaders of the so-called "Big Six" civil rights organizations who were instrumental in the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which took place on August 28, 1963. The other leaders and organizations comprising the Big Six were: Roy Wilkins from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; Whitney Young, National Urban League; A. Philip Randolph, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; John Lewis, SNCC; and James L. Farmer, Jr. of the Congress of Racial Equality.[63] The primary logistical and strategic organizer was King's colleague Bayard Rustin.[64] For King, this role was another which courted controversy, since he was one of the key figures who acceded to the wishes of President John F. Kennedy in changing the focus of the march.[65][66] Kennedy initially opposed the march outright, because he was concerned it would negatively impact the drive for passage of civil rights legislation, but the organizers were firm that the march would proceed.[67]

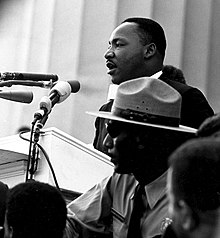

King is most famous for his "I Have a Dream" speech, given in front of the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

The march did, however, make specific demands: an end to racial segregation in public schools; meaningful civil rights legislation, including a law prohibiting racial discrimination in employment; protection of civil rights workers from police brutality; a $2 minimum wage for all workers; and self-government for Washington, D.C., then governed by congressional committee.[70][71][72] Despite tensions, the march was a resounding success. More than a quarter million people of diverse ethnicities attended the event, sprawling from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial onto the National Mall and around the reflecting pool. At the time, it was the largest gathering of protesters in Washington's history.[73] King's "I Have a Dream" speech electrified the crowd. It is regarded, along with Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address and Franklin D. Roosevelt's Infamy Speech, as one of the finest speeches in the history of American oratory.[74]

The March, and especially King's speech, helped put civil rights at the very top of the liberal political agenda in the United States and facilitated passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

No comments:

Post a Comment